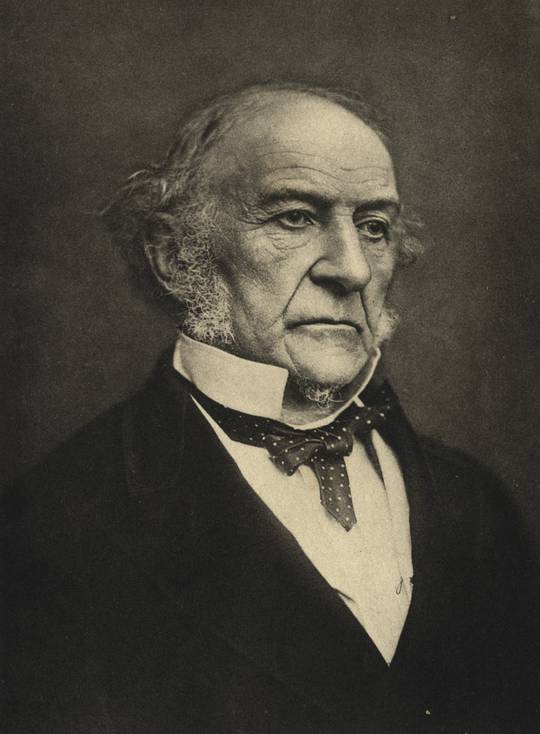

Gladstone (1809-98) like Peel was the son of a wealthy businessman. However, unlike the benign and admirable senior Peel, Sir John Gladstone, 1st Baronet was a major slave-owner, who bought more slave properties at discounts when compensation for slave-owners was proposed in 1824 and received £106,769 compensation from the Slave Compensation Commission after slavery was abolished in 1833, the largest sum paid out by the Commission. His son served as prime minister for a total of 12 years and 4 months, over a period of nearly 26 years, longest of any post-Liverpool prime minister except Salisbury. Over his career, he reinvented himself several times, moving from right-wing Tory to radical Liberal; his rating should take account of those self-reinventions.

As Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1853, Gladstone was much admired, but his reputation is overblown. By the time he took over, the economy was expanding rapidly and the debt to GDP ratio was far below its level earlier in the century. Gladstone was a firm believer in free trade throughout his long career. His sponsorship of the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty of 1860 marked that doctrine’s apogee; the U.S. Morrill Tariff of 1862 made Britain’s free-trade doctrine strictly unilateral.

Gladstone’s advocacy of government economy was legendary, but his multiple attempts to abolish the Income Tax were foolish, especially that of 1874, by when he was moving politically leftwards. Then as now the Income Tax was the most progressive major tax, falling mostly on the rich and the professional classes, while free trade had starved the government of other revenues.

Gladstone’s first ministry of 1868-74 was his best, passing major reforms such as the 1870 Education Act, the abolition of Army commission purchase and the Ballot Act establishing a secret ballot. He also interested himself in Ireland, disestablishing the Church of Ireland and passing a moderate Land Act. In foreign policy, he was pacific, which left Britain as a powerless spectator during the Franco-Prussian war but at this stage had few other ill effects. His ability for hard work, his mastery of detail, his persuasiveness with colleagues and his oratorical abilities all made this first ministry highly successful, although it ran out of steam after 1872.

In 1880 Gladstone conducted the first popular election campaign and won a substantial majority. He passed a radical Irish Land Act, which damaged property rights without pacifying the Irish, as well as a third Reform Act, which improved on the first two by including negotiations with the opposition and compromises on contentious issues. In foreign policy, having campaigned in 1876 against the “Bulgarian Atrocities” allegedly committed by Turkey, he became increasingly moralist, and suffered a major PR defeat (albeit trivial in geopolitical terms) in 1885 with the loss of General Charles Gordon (1833-85) in the Sudan.

Having been defeated at the 1885 election, Gladstone then turned to Irish Home Rule, to attract the support from Irish MPs that would bring him back to power. This was a sensible measure, that would have been much better proposed in 1868 or 1880, with a fresh electoral mandate, avoiding the need for the property rights destruction of the 1881 Land Act, for example. As it was, by introducing the measure for reasons of parliamentary expediency, failing to consider properly the position of Ulster, and then re-introducing the measure in 1893, again without a majority, Gladstone made the question far more politically toxic than it needed to be. Thereby he poisoned Irish administration for over 30 years, eventually leading to civil war and the full independence of an anti-British southern Ireland.

Gladstone’s third and fourth administrations were short, unsuccessful, and dominated by the Irish Question; they do not add to his reputation. As prime minister, the highly successful first ministry and moderately successful second ministry must be balanced against foreign policy failures and what eventually became disaster in Ireland. Gladstone, with a discount for governing in mostly quiescent times, should rank modestly above average, above Disraeli and Russell but below Palmerston and Salisbury.