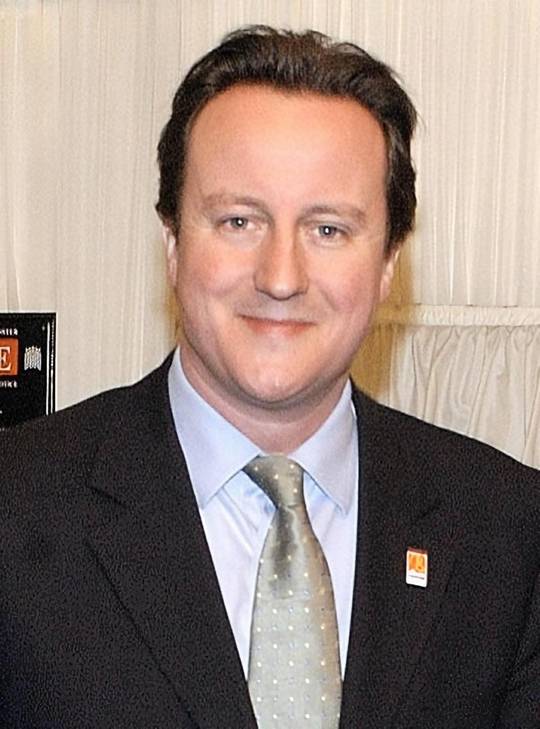

Cameron (1966- ) was the son of a wealthy stockbroker, educated at Eton and Brasenose College, Oxford, where he got a First in the inevitable PPE, socializing at the badly behaved Bullingdon Club rather than the Oxford Union. He then joined Conservative Central Office, becoming assistant successively to Norman Lamont and Michael Howard, (1941- ) before moving to private sector public relations at Carlton Communications. He entered the Commons for the safe seat of Witney in 2001, then was rapidly promoted by Howard, who became leader in 2003. After the 2005 election, Howard pushed forward Cameron and another liberal Conservative MP George Osborne (1971- ) who became Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer while in December 2005 Cameron was elected leader as the modernizing candidate over the considerably older David Davis (1948- ).

For traditional Tories, Cameron was altogether too modern in his period in opposition to 2010, adopting socially liberal positions, engaging in environmentalist stunts, proclaiming an undefined “Big Society” and instituting an “A” list of candidates which gave Conservative Central Office far too much influence over candidate selection and resulted in some low-quality Blairite Conservative MPs that gave trouble in 2017-19 and subsequently. However, he did take the Conservatives out of the European Parliament’s Euro-federalist European People’s Party grouping in 2009.

After he formed a coalition following the 2010 election with Nick Clegg (1967- ) of the Liberal Democrats, Cameron sobered up, pursuing a policy of mild fiscal austerity (public spending declined from 43.8% of GDP in fiscal 2010 to 40.1% of GDP in fiscal 2016). Alas, the truly awful independent monetary policy pursued by the Bank of England, which left real interest rates hopelessly negative and caused British productivity to decline as it had never done before in industrial times, blotted Cameron’s economic track record. His overall record was also blotted by his enthusiasm for intervention in Libya in 2011, which even by Middle East intervention standards was a disaster, leaving that country without a functioning government. On the other hand, the 2014 referendum he held on Scottish independence resulted in a win for the unionists, his desired outcome.

Cameron won a modest outright majority in 2015, then in 2016 corrected the mistake John Major had made by allowing British voters a referendum on membership of the EU. However, when the vote unexpectedly went narrowly in favour of “Brexit” he resigned the leadership, in a gesture of moral cowardice that was highly damaging to Britain’s prospects. Having authorized the referendum, he should have been prepared for either result.

It is again too early to assess where Cameron fits in this list, though one can guess his final placing will be below the middle of the table, with his objection to the Brexit referendum’s results reducing the credit he should get for arranging it.